Foundation

Nov. 4th, 2010 09:16 pm Rereading Isaac Asimov's Foundation last week, probably for the first time in 20+ years, was an interesting if slightly problematic experience. Despite not being visited by the suck fairy, the book's almost complete lack of female characters means it totally fails the Bechdel Test, and its prose is, in places, extremely clunky. The technology has a wonderfully dated 40s feel, featuring space ships with pneumatic tubes and scientists with slide rules, along with a technology base were everything from cities to hand torches is atomic. But I'm going to take a deep breath and ignore all this on the grounds that the book was written in the 1940s, Asimov was at the start of his career, and it's unreasonable to judge the book by today's standards.

Rereading Isaac Asimov's Foundation last week, probably for the first time in 20+ years, was an interesting if slightly problematic experience. Despite not being visited by the suck fairy, the book's almost complete lack of female characters means it totally fails the Bechdel Test, and its prose is, in places, extremely clunky. The technology has a wonderfully dated 40s feel, featuring space ships with pneumatic tubes and scientists with slide rules, along with a technology base were everything from cities to hand torches is atomic. But I'm going to take a deep breath and ignore all this on the grounds that the book was written in the 1940s, Asimov was at the start of his career, and it's unreasonable to judge the book by today's standards.Of the stories themselves, my favourite by far is the opener, which sets up the empire and the galaxy's predicted decent into a new dark age. The planet of Trantor has a great feeling of immediacy and Gaal Dornick's feelings of amazement upon his arrival, like a hick from the provinces arriving in Rome at the height of the empire, carry through to the reader. Hari Seldon is quickly established as a latter-day prophet, ruthlessly wielding the powers of psychohistory with something like omnipotence to create the initial encyclopedia foundation on the very edge of the galaxy.

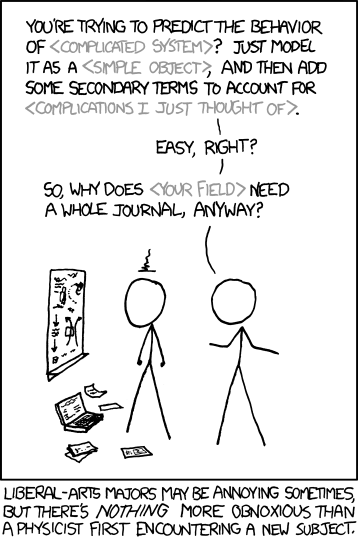

Which seems like reasonable point to jump off into a quick discussion of psychohistory and its problems. Looked at from a modern perspective the whole concept looks distinctly odd, like a bizarre mashup of orthodox Marxism and the kinetic theory of gases somehow accurately implemented by a group of people who lack any form of computing technology more advanced than a slide rule. In a lot of ways Asimov's approach to sociology is characteristic of the attitude of physical scientists to problems in the humanities, as XKCD points out:

Asimov, in Foundation at least, seems to treat the idea of psychohistory uncritically. Seldon's pronouncements, when the come, are spot on and we are lead to believe that even though events are shaped by strong individuals whose behaviour cannot be predicted by psychohistory, Seldon's hidden hand has twisted events such that only one course of action remains open to them. While I know that Asimov was writing before Edward Lorenz and before Popper's The Poverty of Historicism, the whole idea of modelling and shaping societies over hundreds of years must have seemed outre even in the 40s.

Of the remaining stories, all are perfectly serviceable, but none of them have the same impact as the initial story. The science cloaked in religion idea that Salvor Hardin uses to control the four newly independent during the second Seldon Crisis worlds is interesting, but I think Asimov handles the idea better in his Powell and Donovan short Reason, while Hober Mallow's idea that a war can be won through an economic boycott during the third crisis isn't really explored in sufficient depth.

But what really works well for me is the background; the decline and fall of the empire. Like the Roman Empire, it finds itself contracting by degrees after abandoning new ideas and scientific development in favour of conservatism and consolidation — an attitude which the Foundation itself confronts and rejects during the first crisis when Hardin, representing the forces of progress, overthrows the encyclopedists who stand for the forces of conservatism.